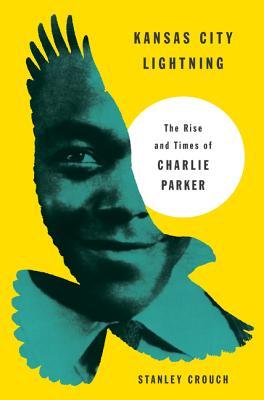

According to the first volume of Stanley Crouch’s masterful biography (Kansas City Lightning, 2013) both parents of the Charles Parker Jr. who largely invented modern jazz could trace at least part of their most visibly African American ancestry to the first peoples of North America.

This seems especially (and perhaps most openly) true of “Charlie Parker’s mother, Addie.” She “was from Oklahoma, the region once called Indian Territory … She was part Choctaw, her Indian blood probably the result of President Andrew Jackson’s policies.”

These policies had led to the infamous Trail of Tears — “a series of forced relocations of approximately 60,000 Native Americans … from their ancestral homelands in the Southeastern United States, to areas to the west of the Mississippi River that had been designated as Indian Territory.” The Trail followed “the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830,” and “included members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations.”

On another account : “Taking place in the 1830s, the Trail of Tears was the forced and brutal relocation of approximately 100,000 indigenous people … Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole … to land west of the Mississippi River. Motivated by gold and land, Congress (under President Andrew Jackson) passed the Indian Removal Act by a slim and controversial margin in 1830.”

African-Choctaw American meets British Indigenous pop tune in late 1930s

On another page of his first volume Stanley Crouch summarizes all this in his account of Charles Parker Jr’s birth : “On August 29, 1920, a brown baby, with a red undertone to his skin, came yowling from the womb …”

It seems that Addie Parker made her only child aware of why his skin had a red undertone — which may help explain his deep attraction to the late 1930s pop tune “Cherokee.” (Charlie Parker is also not the only noted jazz musician with some Native American roots. And he recorded an indigenous blues tune of his own called “Mohawk” in June 1950.)

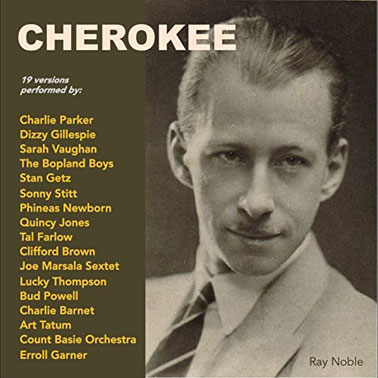

“Cherokee” itself was written by the British bandleader Ray Noble, as the first of five movements in his late 1930s “Indian Suite” (Cherokee, Comanche War Dance, Iroquois, Seminole, and Sioux Sue).

The Noble band recorded Cherokee in 1938. But it was an arrangement of the tune by trumpeter Billy May that became a hit instrumental for Charlie Barnet and His Orchestra — rising to “number fifteen on the pop charts” in 1939.

The road to the modern jazz legend of Ko Ko in 1945 (and 1947)

Charlie Parker would have first heard Ray Noble’s Cherokee on the radio in his late teens, and it does seem to have almost possessed him for much of his early career.

The most celebrated outcome of the possession was a brilliant recording made in New York City on November 26, 1945 — an astonishing “improvisation” on the Cherokee chord changes or harmonic structure, released without the Ray Noble melody as “Ko Ko” to avoid royalty payments.

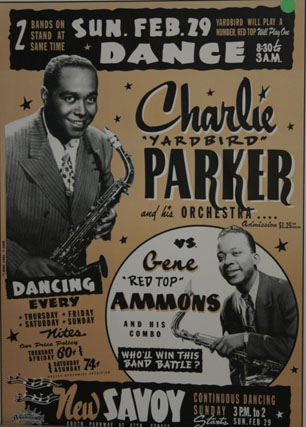

As in many other cases, listening over and over to this late 1945 recording of “Ko Ko” — and then actually trying to play the transcription in the Charlie Parker Omnibook (first published in 1978) — is what finally helped me understand just why Charles “Yardbird” Parker Jr (1920-1955) was such an awesome innovator, in the modern jazz that took shape between 1940 and 1970 and still haunts us today (and perhaps especially) in 2020.

This November 26, 1945 “Ko Ko” quickly became a legend among the early aficionados in New York, Chicago, Kansas City, New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and beyond (Toronto eg), who first recognized and proselytized “Bird’s” genius. A second version of “Ko Ko” was recorded at a Carnegie Hall concert in New York in 1947.

Two earlier expressions of Charlie Parker’s Cherokee possession

To me the Carnegie Hall Ko Ko recording of 1947 is somewhat less commanding than the 1945 original. It makes eminent sense that a written transcription of the 1945 recording is what appears in the Charlie Parker Omnibook of 1978.

Much more recently, however (and largely through the often astounding musical resources that now appear on YouTube), I have discovered (along with many others) at least two earlier expressions of Charlie Parker’s Cherokee possession, that retain the Ray Noble melody as part of the performance.

They certainly do not surpass the 1945 Ko Ko or in any way contest its status as the first great expression of the Yardbird’s talent and defining contribution to modern jazz. But the late great baritone saxophonist and arranger Gerry Mulligan much later reported :

“Somebody sent me a little bit of tape that had Bird playing at home when he must have been maybe seventeen years old or something with a friend of his, a guitar player, and of course he was playing ‘Cherokee.’ This was his number, man, he worked on that thing for years. Somebody said that when he did ‘Ko-Ko.’ It was not just a little accident that it came out the way it did. He had been layin’ for that thing for twenty years anyway. The solo he played on that is like a masterpiece in itself.”

Jay McShann Orchestra recording of Cherokee featuring Charlie Parker?

Both the early Charlie Parker Cherokee recordings I have recently stumbled across myself illustrate just what Gerry Mulligan is talking about here.

(Allowing that “layin’ for that thing for twenty years anyway” is in an honoured older musician’s hyperbolic recollection : Cherokee was only first recorded in 1938 when the Yardbird was 18, and he recorded the original Ko Ko in 1945 when he was still only 25.)

The first of my early Charlie Parker Cherokee recordings is said to be by the Jay McShann Orchestra “featuring Charlie Parker.” This was the blues and swing big band based in Parker’s Kansas City hometown that he cut at least several of his musical teeth with in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

A gentleman called Rob Chalfen, commenting on the YouTube posting by jon ancker, claims that the group playing here is “not McShann, but house band at Monroes in NYC with someone named Tinney on piano, about ’42.” Mr. ancker appears to accept this claim, but I am far from dead certain myself. No one seems to dispute that it is Charlie Parker playing an extended alto sax solo on Cherokee (preparing for Ko Ko a few years later).

The 1942 (or 1941?) Kansas City Trio recording (and free transcription on the Net)

My second early Charlie Parker Cherokee recording seems at least very close to Gerry Mulligan’s “ little bit of tape that had Bird playing … with a friend of his, a guitar player.” And I think it’s considerably more interesting than the Jay McShann or Monroe’s house band recording of (maybe) “about ‘42.”

The documentation on the YouTube posting of this version of Cherokee reads : “Vic Damon Studios, Kansas City, September 1942 … Charlie Parker (alto sax), Efferge Ware (guitar), Little Phil Phillips (drums). There is also some reporting on the Net that sets the date in 1941.

I have stumbled across two further resources for understanding this early 1940s Kansas City trio version of Charlie Parker’s Cherokee. One is some interesting commentary from the young UK alto saxophonist Sam Braysher on what (to further complicate the universe) he suggests is a tune recorded in 1943, that certainly sounds like the YouTube “September 1942” version. The other resource is a free five-page transcription of what certainly is the YouTube “September 1942” version of Charlie Parker’s part in the Kansas City trio recording. (Although this transcription itself suggests 1942 or 1941 as the recording date.)

Of course the early 1940s trio version of Cherokee is not up to the same elevated standard as the 1945 quintet version of Ko Ko. It is part of the preparation for climbing the mountain not the ultimate climb itself. On the other hand, it is probably more immediately accessible for a somewhat broader audience than Ko Ko. And yet, at the same time, I have recently been trying out the new five-page transcription. And I can report that, as usual, attempting to play such things at all adequately remains a force for deep humility in my experience, at the very least.

Tags: Addie Parker, Bird, Charlie Barnett, Charlie Parker's Cherokee, Gerry Mulligan, Jay McShann, Ko Ko, Mohawk by Charlie Parker, Ray Noble, Stanley Crouch, Trail of Tears, Yardbird

Recent Comments