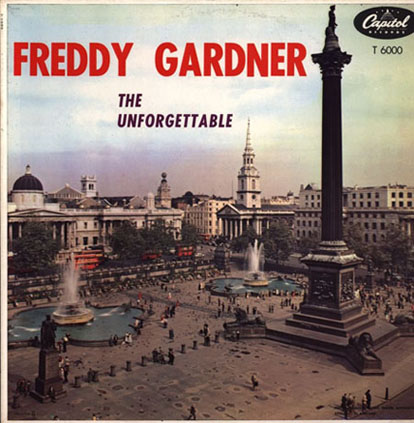

Back on August 21, 2016 (when Barack Obama was still happily President of the USA) one so-called Wile E. Coyote reviewed a two-CD collection of some 51 tunes by the noted UK alto (and other) saxophone artist Freddy Gardner (1910–1950).

Mr. Coyote wrote : “Freddy Gardner had been the consummate alto saxophonist in England during the dance band years … Granted, those interested in alto saxophone recordings expecting something similar to Charlie ‘Yardbird’ Parker will be disappointed, as Gardner plays more in a ‘concert’ style.” He was “nonetheless a virtuoso on his instrument.”

* * * *

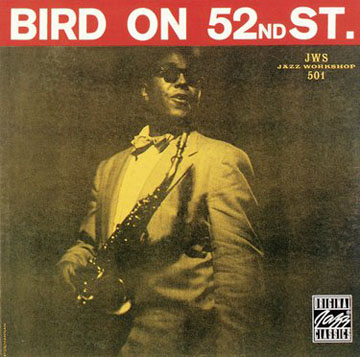

I grew up in a half-old-school Canadian world of the late 1950s and early 1960s where Freddy Gardner and not Charlie Parker was the exemplary alto saxophone artist. It was not until my late 20s and even 30s, I think now (in my late 70s), that I finally seriously discovered the altogether awesome brilliance of Charlie Parker — on recordings and in Omnibook transcriptions.

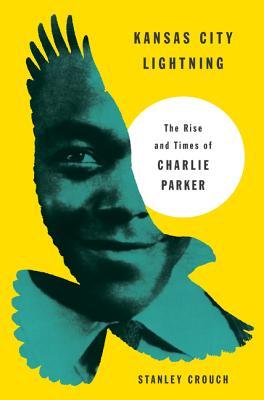

All too many years after this discovery, I certainly know that, whatever else, Freddy Gardner was not Charlie Parker’s successor (he was 10 years older, for one thing, and died about five years before) or even a serious precursor. There are nonetheless a few intriguing parallels. (Once you set aside the disparate hard facts that Freddy Gardner was born in London, England in 1910 and Charlie Parker in Kansas City, Kansas in 1920.)

To start with, both men were recognized more or less early in their careers as the leading alto saxophone players in their respective musical worlds. Gardner was (again) “the consummate alto saxophonist in England during the dance band years” (1930–1950 in Gardner’s particular case), with special reference to London. Parker was the same in the USA, with special reference to New York City (where he was happiest and would finally die), c. 1940–1955.

Tragically early deaths in their 30s is something else that Freddy Gardner and Charlie Parker shared. Parker died in his mid 30s, Gardner when he was 39.

Recent Comments